Peter Dankmeijer: The Implementation of the Right to Education and LGBT People: First Attempts to Monitor, Analyze, Advocate and Cooperate to Improve the Quality of Schools

Abstract:

In the past 4 years, a new international interest has arisen to combat bullying and discrimination of LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bixual, Transgender and Intersex) people in the education sector. This article describes how this interest arose, and some experiences of the Global Alliance for LGBT Education in monitoring the implementation of the Right to Education for LGBT people, to analyze results and how to use the results to advocate and cooperate for a better quality of schools. The article describes a monitoring instrument and experiences with strategic workshops to analyze monitoring results and developing follow-up strategies including cooperation between LGBTI grass roots organizations, the education sector and governments.

Keywords: LGBT-discrimination; Monitoring; International Strategy; Non-Profit Organisations; Global Alliance for LGBT Education

Table of Content

- The International Right to Education

- Emerging Interest in LGBTI Issues in Education

- Development of a Monitoring Instrument

- Education Strategies in Denying, Ambiguous and Supportive States

- Experiences with Strategic Workshops

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- References

1. The International Right to Education

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN, 1948), abbreviated as UNDHR, was agreed on after World War II to prevent the horrors of interstate conflict and the eradication of defenseless population groups. The general mission of the United nations (UN) since that time is "maintaining international peace and security, developing friendly relations among nations and promoting social progress, better living standards and human rights" (UN, 2014) by setting standards and by cooperation on implementation of State action plans to reach such agreed standards. Thus, setting and maintaining human rights standards are key aspects of the UN mission.

Article 26 of the UNDHR is the Right to Education (UN, 1948). Core quotes of this right are: "Everyone has the right to education. (...) Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace."

The Right to Education has been detailed in a series of conventions. There are five conventions that make references to education: the Convention Against Discrimination in Education (UNESCO, 1960), the Convention on Technical and Vocational Education UNESCO, 1989), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (United Nations, 1976), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1990) and the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) (United Nations, 1979). Conventions set standards and include intentions to implement the agreed standards. Each convention has its own monitoring mechanisms and procedures for States to discuss the implementation, and specific UN bodies are is responsible for guiding this process. The monitoring and dialogue on conventions is in the first place a State affair. Some monitoring and review procedures allow for input by civil society, but others do not or are very unclear about it.

2. Emerging Interest in LGBTI Issues in Education

In the past decade, international politics have seen increasing attention to the rights of people who are discriminated based on Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity (SOGI). There seem to be two reasons. Firstly, LGBTI people have become more self-aware and empowered, and have increased their capacity to advocate within States and on the international level to advocate for their rights. In a growing number of States, LGBTI rights have been agreed on and are now actively supported by governments (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2014). Secondly, the global AIDS endemic has made (unsafe) sex between men an international topic of discussion. Because Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) are one of the "groups" that are most at risk, there has been a growing need to do more research and to develop adequate prevention and care. This is of a great State concern, because the AIDS endemic creates huge health costs and in the long run loss of economic power when the labor forces gets thinner (Bell, Devarajan, Gersbach, 2003; Mandell, Bennett, Dolan, 2010). However, it has become clear that even in the face of such health and economic setbacks, the criminalization of same-sex behavior and the social marginalization of MSM and transgender people are major obstacles to develop effective strategies in a number of countries (International Center for Research on Women, HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination, 2009; NGO Delegation to the UNAIDS PCB, 2010; The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, 2011). The stubborn refusal of some authorities to recognize this and to take adequate measures has led to a huge body of research and a great number of initiatives.

But recognizing SOGI as a human right issue remains an extremely contended area: about half of States take the perspective that human rights are universal and hold that LGBTI people cannot be excluded from such rights. But the other half of the States holds that same-sex behavior is a threat to the social order and - although any person is entitled to human rights - , "asocial behavior" should not be included in human rights protection (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 2014). This "traditional values" position is framed by a range of States and religious NGOs with a discourse in which gender and sexual orientation are presented as "constructions", which are seen as radical ideologies which conflict with a "natural" and traditional social order (Human Rights Watch, 2011 Scanteam, 2013’; Reid, 2013; Article 19, 2013). The international controversy on whether LGBTI people are entitled to human rights when they engage in same-sex behavior or gender non-conforming behavior has resulted in a stalemate: to date, not a single formal reference to SOGI has been made in any convention.

Apart from the lack of mention of SOGI in conventions, making reference to sexual diversity in the context of education is even more sensitive. Most States have long considered "education" to involve not only transfer of knowledge and technical skills, but also of social values and norms and of core importance to national identity (Martens, Nagel, Windzio & Weymann, 2010; Weymann, 2014). There is international consensus that such local values should be respected and that defining the content of education is a local and cultural prerogative of each State . This is called the "subsidiarity" principle. At the same time we see that local "cultural values" may conflict with universal human rights. For example, the cultural value that girls should stay at home and do not need education is in conflict with universal access to education, which is the fundament of the right to education. However this specific value is not so contended anymore: access to education for girls is a long term priority in the Millennium Goals (United Nations, 2014), even though the implementation of this goals remains difficult because of local social resistance.

Most contented are attempts to set international standards for the content of education. At the World AIDS Conference in 2008, it was clearly shown for the first time that the HIV-epidemic could not be combated effectively when stigmatization of LGBT (and other marginalized groups) was not stopped. This conclusion created a wave of initiatives to combat criminalization of same-sex contacts and to explicitly include sexual diversity in sex education programs, most importantly a Ministerial Declaration of Latin American Ministers of Education to provide sex education and to combat homophobic bullying in schools (Ministerial Declaration Preventing Through Education, 2008; SIECUS, 2008). However, when the Special Rapporteur on Education recommended to make inclusive sexual education (including the themes gender, heteronormativity and homophobia) as a mandatory aspect of the right to education (Muñoz, 2010), his report was severely criticized and the recommendations were rejected (United Nations Meeting Coverage, 2010). It was obvious that the UN as a State association is not ready to make international agreements on sex education, even when millions are dying and there is proof that this is partly due to SOGI discrimination.

But even on the content of education, there is some progress in setting international standards. A 2007 judgment of the European Committee of Social Rights condemning the Croatian government for implementing a discriminatory sex education curriculum (Council of Europe/The European Committee of Social Rights, 2007).) is the first jurisprudence which shows that State-supported homophobia in schools can be combated in a legal way on the international level (at least in Europe) and in 2009 the European Council of Ministers agreed with this judgment (Council of Europe, 2009).

UNESCO is the UN organization responsible for education and monitoring the Convention Against Discrimination in Education and the Convention on Technical and Vocational Education. The Global Alliance for LGBT Education (GALE) started cooperating with UNESCO in 2008 and initiated discussions and awareness within the organization. Prompted by this growing awareness and also by the conclusions of the World AIDS Conference in 2008, the UNESCO AIDS Prevention Unit decided in 2011 to embark on a separate strategy on LGBTI issues in schools (UNESCO 2011). GALE has supported UNESCO in this strategy and helped secure a support budget of the Dutch government for it (UNESCO HIV & AIDS, 2013).

Because of the sensitivity of sex education and of same-sex relations in the international arena, UNESCO chose to focus on "combating bullying" as a strategy to get legitimate attention to LGBTI stigma. Bullying is a form of violence, and few States or schools would be willing to openly support or condone violence. Still, at this time the UNESCO strategy and the recommendations on homophobic bullying are "technical" and therefore not political (State supported) guidelines (UNESCO, 2012). The UNESCO strategy is focusing on documenting needs to combat homophobic bullying through research, and by sensitizing UNESCO regional offices. In turn, informal contacts are made with State officials. A growing body of research, growing awareness and a growing network of supportive officials should lead to a high level conference of Education Ministers in 2016, which could potentially lead to international resolutions top combat homophobic bullying.

3. Development of a Monitoring Instrument

In order to develop effective strategies to combat homophobic bullying in schools, but also improve the implementation of the Right to Education on the whole for LGBTI students, instruments need to be developed. GALE studied the research questionnaires used for research on LGBTI issues in schools and concluded to most of them do only measure parts of the right to education. Research is often done by LGBTI organizations themselves or by universities working on behalf of them, or in cooperation with AIDS service organizations. This commonly leads to biases in the surveys towards questions about health and discrimination, and a neglect to questions that are central to education policy like access, drop-out, personal development and human rights education. Also, monitoring of recognition of State laws and guidelines regarding LGBTI issues in the education sector did not exist at all yet.

Therefore GALE decided to develop a new monitoring instrument: the GALE Right to Education Checklist. GALE was inspired by the ILGA State-Sponsored Homophobia Maps (http://ilga.org/what-we-do/state-sponsored-homophobia-report/), which identify which States persecute, recognize or protect human rights for LGBTI persons. Apart from monitoring State regulations, these reports and maps also function as awareness and advocacy instruments.

However, the Right to Education cannot be monitored in exactly the same way as ILGA monitors criminalization, same-sex relationship arrangements, or anti-discrimination laws. States either have such laws, or not. The Right to Education however, is multifaceted. In each State , there are ratified international Conventions, national laws, educational directives and more informal guidelines on a range of public and school authority levels that influence the school practice. An second complication is that it is very common that the actual school practice can be very different from the legal frameworks and guidelines. The consequence of this ambiguity is that the Right to Education cannot really be monitored by using a simple yes/no type of assessment. Third, a final complication is that the definition of the target group is contended. GALE cannot identify its target group as LGBTI, first because it is "colonizing" people in an "identity" that may not want to adopt, and secondly because in many countries the concepts L, G, B, T and I do not exist. Using the acronym MSM (and WSW, Women who have Sex with Women) is also not applicable, because many younger students do not yet have sex and because they are often discriminated based on atypical gender expression rather than on real or assumed same-sex attraction.

As a strategy to solve these dilemma's, GALE chose to develop a framework that is based on the international agreed aspects of the Right to Education. The GALE Checklist (http://www.lgbt-education.info/en/r2echecklist) is a list of 15 statements that reflect principles and indicators commonly used in the five relevant Conventions and in their monitoring mechanisms, including the monitoring of the Millennium Goal "Education for All". The 15 statements represent the most important aspects of the Right to Education, framed in 3 main chapters: the position of students (including access, safe school and protection against bullying), a supportive curriculum and the quality of teachers.

The target group was defined as people who are Disadvantaged because of their Expression of Sexual Preference Or Gendered Identity (DESPOGI). This new acronym is more tailored to educational monitoring purposes that activist, legal or health related acronyms like LGBTI, SOGI or MSM/WSW.

THE GALE CHECKLIST

Does the state secure that:

- The position of DESPOGI students in schools

- DESPOGI students have full access to educational institutions

- DESPOGI students have freedom of self-expression in school

- DESPOGI students are protected against bullying and harassment

- DESPOGI students are supported to prevent drop-out

- DESPOGI students are supported to have an equal level of academic performance

- The availability of supportive curricula

- Public information about sexual diversity is supported

- There is supportive and relevant attention for DESPOGI students in school resources

- There are specific resources for DESPOGI students

- There are support services for DESPOGI students available

- DESPOGI students have informal peer-learning opportunities

- The position of school staff

- Teachers and other staff are supportive of human rights for DESPOGI students and staff

- School staff has adequate competences to teach about sexual diversity

- School staff has adequate competences to support DESPOGI students

- The school environment is supportive for sexual diversity

- There is employment protection for DESPOGI staff

The Checklist is scored on a 6 point scale: (0) No, this is forbidden or denied, (1) There is no clear policy on this, but it is discouraged, (2) There is no policy on this, (3) It is encouraged, but there is no clear policy on this, (4) Yes, there is evidence to support this, and (5) No data available. To calculate a general indicator, we add the number of each given answer (excluding the answers scored as "no data") and divide the total score through the maximum score of 60 to get a percentage. This percentage roughly represents the extent to which a state implements the right to education for DESPOGI people, even though the percentages per checkpoint may vary widely. On the GALE World Map (www.gale.info/worldmap) GALE present states as "denying", "ambiguous", or "supportive". States with the highest number on the combined scores 0+1 are labeled "denying", with score number on 2+3 as "ambiguous" and states that score highest on 4 as "supportive".

The first monitoring of the situation in States is still in progress.

4. Education Strategies in Denying, Ambiguous and Supportive States

During her monitoring and support contacts with a range of LGBTI groups, Family Planning and AIDS service organizations, education staff and government officials, GALE noted some interesting impressions about contexts, goals, strategies and interventions in denying, ambiguous and supportive States (Dankmeijer, 2012). In this paragraph we offer a tentative typology and analysis, but it should be kept in mind that the division in three levels is a gross generalization which is more helpful for awareness purposes than it is (currently) based in in-depth research on national education policies and contexts.

In "denying" States, attention to sexual diversity is forbidden and/or socially taboo. The environment is not safe enough to discuss sexual diversity openly and LGBTI organizations have to take safety precautions to protect their members and human rights activists. This is certainly true when focusing on education. Most "denying" states are bound to have a bad human rights reputation in a more general way as well and this will also show in more generally unsafe school environments and support ore exclusion of specific social groups. It may be that even the concept of human rights is (partly) rejected, preferring local "traditional" harmful and discriminatory practices above self-determination and safety of individuals. In denying States, there are both legal and social risks involved in attempting to do educational work. Changing attitudes through education is difficult because they may represent an almost complete negative norm, which makes a dialogue on diversity very challenging. Some of the denying States are very poor, which poses challenges because local donors will not fund projects and students or teachers will not be able to pay fees for training. Even voluntary peer education will be difficult because coming-out is dangerous. LGBTI organizations may be small and with limited expertise, certainly on formal education but often also on more basic competences like storytelling, bookkeeping, cooperation or project management. It may be difficult to recruit volunteers because DESPOGI people may have low wages and may have to work more than regular hours to survive.

In dying States GALE found it important to build a base for initiatives. The first need among activists is often to know more about themselves: who are we? Why do we feel this way? Why can we not express our feelings? Why is this social pressure to deny our feelings and sexuality? How do we relate the answers to these questions to local and international definitions of sexual diversity? The most useful initial goal at this stage is to find answers to such questions, to become empowered to express feelings, and to create solidarity to create space for self-expression in society. This awareness is always first an internal goal in LGBTI circles, and may later on become an external goal for public education. Concretely, LGBTI organizations often start with self-help groups or services, where members or visitors can share stories in a safe space. These safe spaces lead to empowerment. The stories shared here can be documented (anonymously) and disseminated more widely, even in public environments like websites, dissemination of a summary in the shape of a comic book, or in informal education to limited and invited audiences. LGBTI activists who want to take a next step after this stage, could be gathered in a new education group which develops further activities. Such a group could initiate more systematic story collection, simple quantitative research to check and to show that the discriminatory patterns in stories are real problems among the population, and undertake dissemination of such information to potential allies.

In "ambiguous" States, there are usually no formal prohibitions to offer information about sexual diversity. Indeed, often LGBTI organizations do offer information in various ways, like through visibility campaigns to create awareness (posters, leaflets, video clips) or by developing specific curricula and resources for schools on sexual diversity and offering informal education by volunteers or even some teacher training. On the other hand, the state does not take the lead in this and support for LGBTI-led interventions may be lacking or be ambiguous. The result of this is usually that the education sector regards sexual diversity as a private interest of some marginal advocacy groups and not of mainstream interest. Efforts of DESPOGI organizations then often remain limited in quality (because of limited educational expertise) and scope (because of the lack of political and educational backing, networks and funding).

In ambiguous States, LGBTI organizations tend to turn their internal empowerment and awareness processes into concepts for public education and student support. In practice, they may create informal self-support and activist groups (Gay/Straight Alliances), (peer) education or media campaigns in which they more or less directly replicate their internal coming-out process and demands. This type of education is "sender" - centered: the experiences of DESPOGI people and their wishes or demands are presented in the education programs. However, access to regular schools with this type of education often remains very limited, partly because more effective programs are "receiver"- or "learner"- centered. Advocacy may be counterproductive when it is singularly focused on specific LGBTI demands and when it does not take into account the potential for real innovation; for example by visible integration of sexual diversity in more general anti-bullying strategies, sex education and citizenship education, and by making teachers and other educationalists owners of the strategy and resources. Cooperation between the LGBTI movement and the education sector may be challenging when it is characterized by ambiguity about goals, about acceptable content of education and about different views on the roles and willingness of stakeholders. There are often varying views within the LGBTI communities and the wider society on who is the enemy, who are allies, and who can be trusted in cooperation. For example, LGBTI groups providing different types of services may not be able to agree on a combined strategy because they fear competition to their own interventions. They may also find it difficult to work with the government or educational officials when they are unable to engage in a constructive dialogue on shared needs: often the educationalists focus on a wider frame to embed SOGI issues in, while the LGBTI movement often focuses on specific visibility of their concerns.

However, the very ambiguity also offers lot of opportunities. Inevitably, there will be at least some - and usually a growing number of - allied experts in the government and in the education sector. There is some willingness and space, and the challenge is to find the allies and the appropriate spaces. A major goal for NGOs in ambiguous States is to explore what both DESPOGI and heterosexual students and teachers want and need. The common needs can lead to alliances, piloting interventions and creating a basis for continued (mainstreaming) cooperation when ambiguity turns into support.

"Supportive" states have decided that combating homophobia and transphobia is a relevant policy issue. Such states develop a program to mainstream attention for sexual diversity in the education sector. The way they do this will depend on the strength of the government leadership, the internal resistance in the Ministry of Education and in the education sector itself, and on the cooperation with experts in SOGI issues and the LGBTI movement.

At this stage, we note that differences in roles become more pronounced. The LGBTI movement, which until this stage has been very active in both advocacy and in development and implementation of education itself, has to reposition their own education work and the type of advocacy, in order to make space for ownership of the education sector and the Ministry of Education itself. The government and especially officers from the Ministry of Education and from national education institutions start to formulate own ideas and strategies. Even when the general policy context is now supportive, the interplay between LGBTI activists, experts, government officials and top-level education officials is usually a mix of support, cooperation, uneasiness, irritation and sometimes competition. One aspect of this concerns the content of education. The shift to mainstreaming means that attention to sexual diversity is being integrated in regular education. This implies it needs to fit in existing (sometimes less adequate) contexts and that the "specific" attention becomes a matter of course and less thematic, which may be considered insufficient by activists. Another challenge is the process of mainstreaming. Who will take the lead in this? Of course all stakeholders want the power to steer this process. This may lead to competition. Also, this may be the first time when regular (i.e. straight) educationalists and (LGBTI) activists are really starting to work together. Experience with these processes shows that the differences in interests (goals), ideology or theoretical frameworks and working cultures may be frustrating.

It is essential that the government and the Ministry of Education take the lead in the mainstreaming process, that the LGBTI movement and experts are positioned in an adequate consulting position and that the educational sector itself becomes involved in co-development. This is often done by the formation of one or more national advisory committees which undertakes field consultations, networking conferences, the formation of a national LGBTI/Mainstream Alliance. The most important aspect of successful innovation is that the educational professionals who are responsible to implement the new interventions should be co-responsible for the development. They need to feel that they own the innovation, otherwise it will not be sustained. A second important criterion for successful innovation is that professionals are supported in the process of change, starting with "early adopters" and sharing successes, then involving "late adopters" and finally enlisting "laggards" (people who tend to remain resistant to change) (Rogers, 1995). Thus the essence of mainstreaming strategies is to create ownership and facilitate long-term change processes.

Leadership by the Minister of Education and top-ranking educational officials is very important. Such leadership is shown by public statements and field visits, strategy development, funding and international cooperation in promoting human rights in education.

Examples of mainstreaming activities are a the Guidelines of the Dutch School Inspectorate on integration of sexual diversity in school policy ("Iedereen is anders", "Everybody is different") (Dankmeijer, 2003), and a the Irish guidelines for the youth sector (Office of the Ministry for Children and Youth Affairs/BelongTo (2011).

5. Experiences with Strategic Workshops

To stimulate local actors in assessing their needs on educational strategy and assist them in making strategic choices, GALE developed a strategic workshop. Three strategic workshops were organized in South East Asia in May 2013, one in Nepal in August 2014 and 3 others in late 2014 in Argentina, Greece and Finland. This paragraph explores the results and possible follow-up of these workshops.

The general program of the workshop is an introduction to the right to education, filling in the GALE Checklist or discussing results of an assessment done before the workshop, identifying supportive factors and challenges, setting priorities and exploring strategies and cooperation. Ideally, the workshop takes at least one or maybe two days. Also ideally, the workshop is attended by both LGBTI activists, educational officials and teachers, and officials from the Ministry of Education. However, until now the workshop has mostly been implemented in Asia in denying and ambiguous States. In such contexts it was too difficult to engage the Ministry of Education, but sometimes we could involve teachers, universities, curriculum development institutes and local educational administrators.

In Indonesia, the workshop was organized by Arus Pelangi, a LGBT organization in Djakarta. The workshop was attended by 15 activist representatives from different parts of Java and Sumatra, of whom some where teachers themselves. There also was a director of a national anti-bullying organization "Yayasan Sejiwa". After the strategic workshop, they also asked GALE to offer a peer education training, which proved to be a fruitful combination because the more concrete learning experiences in the peer education training had direct relevance to solve some strategic dilemma's.

After the analysis phase of the strategic workshop, the participants concluded Indonesia should be categorized as a denying State and Indonesian schools suffer from a general violent school environment. Islamic forces are slowly taking over the government and suppress diversity and human rights. It is quite common to have battles between groups of students of different schools, and students dying of injuries. This is seen as a problem, but no-one seems to have a solution. Teachers erroneously still believe that corporal punishment is good pedagogy and this type of discipline results in role modeling to students that you can get what you want through force. Although the national Indonesian creed is “Unity in diversity”, nor teacher nor students learn how to deal with diversity or conflict and this creates serious challenges in Indonesian society. Social exclusion of DESPOGI and especially discrimination of transgenders (Waria) should be seen as part of this social dynamic. After a strengths/weakness analysis, the general consensus was that combating violence and bullying, and extending this strategy to diversity pedagogy, would offer the best opportunities. If the Indonesian movement would develop this choice, it would follow the lead that UNESCO has taken until now. Although government officials declined to participate in the strategic workshop, Arus Pelangi and GALE visited the Indonesian UNESCO staff the day before, which resulted in surprise that this issue could be raised in Indonesia and a lot of questions, but also in interest to further explore the issue and potential cooperation. The director of Yayasan Sejiwa decided to cooperate with Arrus Pelangi and other LGBTI NGOs to offer them access to mainstream institutions and to the government (Dankmeijer, 2013).

The following two-day peer education training made the aspirant peer educators aware of the difference between combating "homophobia and transphobia" and "to nuance heteronormativity". The first is an "adversary" perspective, while the second allows for a dialogue on shared concerns and goals with students. The participants reflected on their own position in relation to heteronormative values and became more conscious of realistic and feasible objectives for peer education sessions. In addition, the participants learned how to deal with aggressive emotional responses and with groups that remain silent because of taboos, how to deal with prejudiced questions and which simple or more advanced methods can be used for different target groups. Finally, concluded that aggressive and silent responses are not unique for students. The concrete learning experiences on how to deal with such responses were found to be also useful in advocacy or potential strategic cooperation with mainstream (heterosexual) allies and in relations with "enemies" (Dankmeijer, 2013).

The follow-up of the workshop was the development of two peer education programs, cooperation on an anti-bullying strategy and the development of a new advocacy in the area of education.

In Vietnam, a strategic workshop was organized in Hanoi by The Center for Creative initiatives in Health and Population (CCIHP), which is formally a mainstream NGO by very active on lesbian and gay issues. The workshop was attended by about 70 representatives from a range of civil society organizations (both mainstream and gay/lesbian), educational institutions (including a university, teachers and the institute for curriculum development), two ministries and a few UN officials (Dankmeijer, 2013).

The core of the analysis made was that despite all the initiatives of both the (communist) government and civil society, it is a challenge to properly implement life skills education including attention to sexual diversity. The government is progressive, but also authoritarian and most of the rural population is socially conservative. In this sense, Vietnam is an ambiguous State, but with potential to become supportive soon.

The main recommendation was that it would be welcomed if the government takes leadership and make such implementation, including "dealing with diversity" a clear priority. of the main challenges in Vietnam is the quality of teachers: how can teachers be trained to make the shift from just transmitting facts to more interactive ways to involve students in learning and a focus on real life skills? It emerged that a key competence to be a good citizen is to learn to decide what you want, to express this adequately and to be flexible in dealing with new situations, unexpected events and with people who have different opinions. This is "dealing with diversity". This link between diversity education and key "transversal" life skills competences, may be the best argument to engage in dialogue between mainstream and LGBTI civil society and the government.

There was also a two day peer education training in Vietnam (Dankmeijer, 2013), this time with a mixed group of lesbian/gay and heterosexual young people. The workshops resulted in peer education in schools and increased cooperation between the national institute for curriculum development, Hanoi university, and a range of adult and young people's organizations. The Ministry of Education seemed to feel slightly intimidated by enthusiasm of civil society organizations. Ministry officials engaged on an own initiative to explore integration of LGBTI issues in life skills education, but it remains to be seen if the two strategies will connect and if enough trust can be created to make Vietnam a supportive State.

In China. the strategic workshop was organized by the Beijing LGBT Center in cooperation with Common Language, an organization that already offers informal education sessions to university students (Dankmeijer, 2013). It was attended by 15 activists, teachers, school counselors and a representative of UNESCO in China. The participants were quite inspired by the tentative description of the differences between denying, ambiguous or supportive States. They analyzed that China was somewhere in the early stages of the ambiguous phase. That is to say: the Chinese government does not forbid anything, but may act repressive of completely disinterested. For the Chinese LGBTI organizations, who are emerging from a denying situation, this is a challenge. Their impulse is to organize provocative ad hoc actions, like street performances and online videos that test the limits of State censorship. This is the way they are used to challenge the denying situation and make LGBTI needs visible. This strategy has regularly lead to the police trying or succeeding in cancelling the event, often without argument. There is no direct contact with the government or specifically with the Ministry of Education. At the start of the workshop it was perceived that a dialogue was impossible.

One of the processes developing during an ambiguous phase is that LGBTI organizations slowly evolve from enemies of the government to cooperation partners. This was a new and refreshing perspective for the Chinese participants, which inspired them to think about how adapt their goals, strategies and advocacy methods. They decided more research is needed about the educational goals, challenges and strategies of the government. Such data would enable the LGBTI movement to better link into mainstream priorities and to "frame" their needs into education policy language. Examples of such framing could be to link into the government priority for HIV-prevention, sexual health and teaching "interpersonal skills". The discourse on this could be framed as "harmoniously living together" in diversity rather than promotion of sexual diversity as a specific priority, because "harmony" is the traditional core value of the Chinese government.

The workshop concluded with the recommendation to follow-up this analysis by starting a strategy development project, in which activist organizations work together with UNESCO, UNDP, universities, some secondary schools and if possible with government officials to research and develop in a joint strategy plan that is acceptable for all stakeholders and that offers a space for small scale experiments on sexual diversity education hat link into mainstream guidelines and policies.

In Nepal, the strategic workshop was held at the end of a train the trainer course for (heterosexual) teachers (Dankmeijer, 2014). There were 18 teachers who were part of the "Chetana" teacher group, which offers training on LGBTI issues to mainly rural schools in the central region of Nepal, around Pokhara. One participant was the director of the local branch of the Blue Diamond Society, the main LGBTI organization in Nepal, which cooperates closely with Chetana.

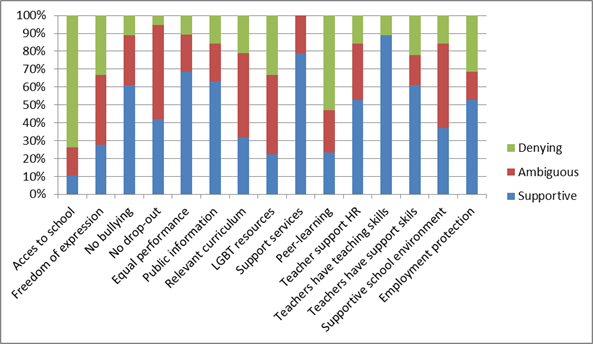

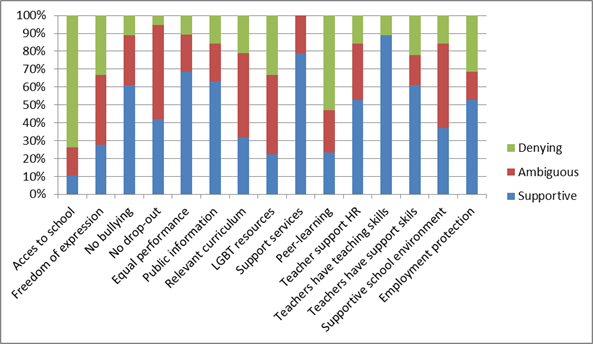

The participants started to score Nepal on the GALE Checklist. The average score of the 19 participants was 2,36, which would label Nepal as an ambiguous State. However, although calculation of averages results in ambiguous scores, a majority of the checkpoints was scored as supportive. This resulted in the overview given in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Scores of 18 central Nepalese teachers and 1 activist on the GALE Checklist

In the discussion of the results, it emerged that Nepal scores rather denying on "access to school". This was explained by anecdotes about "meti's" (transgenders) who, when they come out at school, are often denied access to the school. This was explained by a lack of knowledge and following negative stereotyping rather than outright negative values. On the contrary, the teachers expect their fellow teachers to be interested in diversity and open to discuss it and to work on school safety. In addition to making their schools more safe for meti's, they often also want to advocate for a clear human rights perspective in the new constitution that is currently being drafted in Nepal. That this view of the Chetana teacher is actually rooted in practice became clear in a second training a week later, when they in turn trained a new group of teachers in the rural village of Galyang. Although these teachers volunteered their free Saturday to follow a training on LGBTI issues, they were still extremely open en curious.

Peer learning was also score quite denying. Most meti's and certainly same-sex attracted Nepalese students will not know where to find other LGBTI young people or support groups and have to rely on dating sites where most members try to remain as anonymous as possible. The pressure of the family to marry (for boys), and parents marrying their daughters off are main obstacles to free expression and personal development.

The teachers were most ambiguous on whether Nepal has a curriculum that is relevant for meti's and same-sex attracted students, and if there are adequate specific resources. This is certainly not yet the case, but if teachers are aware, they would be able to offer such information. Another aspect is that the Blue Diamond Society has been in contact with the national institute for curriculum development, which is now working on inclusion of SOGI issues in the formal curriculum.

Because this strategic workshop lasted only for two hours, there was no time to engage in a proper strengths/weakness analysis or to come to strategic recommendations. However, during the days and weeks afterwards, GALE, Chetana and the Blue Diamond Society developed follow-up plans to improve the quality and expand the number of teacher trainings. In addition, it was decided to do more research among teachers and to frame the current successful teacher trainings in a wider strategy on safer and more inclusive schools.

6. Conclusions

The Right to Education is a complex set of standards which is difficult to properly monitor. The content of education, especially human rights education and sexuality education, are controversial in an international context. LGBTI issues currently have no place in the discussions about the Right to Education and the Millennium Goal "Education For All". Still, in recent years, some attention has emerged, partly because of advocacy by GALE and partly because AIDS prevention strategies have proved to be ineffective due to stigma of MSM. UNESCO, with financial support of the Dutch government, has developed a strategy to combat homophobic bullying in schools, which takes the discussion to government levels. The strategy focuses on stopping violence rather than supporting same-sex relations or sex education, which may take the sting out of international controversies.

Whereas the UNESCO strategy focuses on research and general awareness of governments of homophobic bullying in schools, GALE is looking for an even more strategic support of both governments and civil society. To facilitate monitoring of the implementation of the rather un-transparent Right to Education regarding DESPOGI, GALE developed a checklist and a perspective on denying, ambiguous and supportive contexts which proves to be helpful in assessing and planning next steps and to forge cooperation between civil society organizations, the education sector and government officials.

7. Recommendations

This seems to be the right moment for LGBTI organizations, schools and governments to reflect on how we train our young people to be good citizens, who are open and curious, and who are able to deal with new people, situations and with conflicts, including with DESPOGI people and the controversies about SOGI and sexuality in general. There are numerous international and local conflicts that need to be solved by an increased understanding and continuous use of interpersonal skills. While the world seems to be drifting towards wars and hate driven religious and social conflicts, it may seem that such problems cannot be overcome and that LGBTI issues are a "luxury" discussion. However, the dialogues that have started around sexuality and sexual diversity have the potential to show the way on how to really deal with diversity in a globalizing world.

This is not going to happen by itself. LGBTI organizations, just like any other civil society organizations, schools and governments, need to start looking further than just their own organizational interests. By engaging in an open dialogue, analyzing contexts, exploring common needs and deciding on how to cooperate on how to most effectively reaching common goals, a world can be won and a new momentum can be given to the modern importance and the full implementation of human rights.

8. References

Article 19 (2013). Traditional Values? Attempts to censor sexuality: Homosexual propaganda bans, freedom of expression and equality. London: Article 19 Free Word Centre (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.article19.org/resources.php/resource/3637/en/traditional-values?-attempts-to-censor-sexuality.-homosexual-propaganda-bans,-freedom-o-f-expression-and-equality)

Bell, C, Devarajan S, Gersbach H (2003). "The long-run economic costs of AIDS: theory and an application to South Africa" (PDF). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3152. Retrieved April 28, 2008

Council of Europe/The European Committee of Social Rights (2007). International Centre for the Legal Protection of Human Rights (INTERIGHTS) v. Croatia (Checked at http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/socialcharter/Complaints/Complaints_en.asp; case 45/2007)

Council of Europe (2009). Resolution CM/ResChS(2009)7. (Checked on 9 November 2014 at https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?Ref=CM/ResChS%282009%297&Language=lanEnglish&Ver=original&Site=CM&BackColorInternet=C3C3C3&BackColorIntranet=EDB021&BackColorLogged=F5D383)

Dankmeijer, Peter (2003a) Iedereen is anders. Een handreiking van de Inspectie van het Onderwijs om scholen veilig te maken, in het bijzonder voor homoseksuele leerlingen en docenten, Inspectie van het Onderwijs, Utrecht, september 2003

Dankmeijer, P. (2012). Full development of the human personality and respect for human rights. A Guide to Monitor the Right to Education and Strategy Development for Sexual Diversity. Amsterdam: Global Alliance for LGBT Education (GALE) Checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.lgbt-education.info/doc/gale_products/GALE_MONITOR_RIGHT_TO_EDUCATION_GUIDE.pdf)

Dankmeijer, P. (2013). Articles on GALE workshops by Peter Dankmeijer in SE Asia, May 2013. (Checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.lgbt-education.info/doc/Asia/GALE_Strategy_workshops_and_training_peer_education_in_SE_Asia_%20(May_2013).pdf

Dankmeijer, P. (2014). Nepalese Chetana teacher group organizes strategic workshop. (Checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.lgbt-education.info/en/news/local_news/news?id=780)

Human Rights Watch (2011). Joint NGO statement on traditional values

UN Human Rights Council Advisory Committee at the 7th Session – August 2011. New York: Human Rights Watch

International Center for Research on Women, HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination: MacQuarrie, K., Eckhaus, T., Nyblade, L., (2009). A Summary of Recent Literature. (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/20091130_stigmasummary_en.pdf)

International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association: Itaborahy, L.P. & Zhu, J. (2014). A world survey of laws: Criminalisation, protection and recognition of same-sex love. Geneva: ILGA, May 2014 (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://old.ilga.org/Statehomophobia/ILGA_SSHR_2014_Eng.pdf)

Mandell, G.L., Bennett, J.E. and Dolan, R. (2010) Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th Edition. London: Churchill Livingstone (Chapter 117)

Martens, K., Nagel, A., Windzio, M. and Weymann, A. (2010): Transformation of Education Policy. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Ministerial Declaration Preventing Through Education (2008) (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/Santiago/pdf/declaration-preventing-education-english.pdf)

Muñoz, V. (2010). Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to education. A/65/162. (checked on 9 November 2014 on http://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/UNSR_Sexual_Education_2010.pdf)

NGO Delegation to the UNAIDS PCB (2010). NGO Delegation Annual Report tot the UNAIDS Board: Stigma and Discrimination: Hindering Effective HIV Responses. Geneva: presented at 26th UNAIDS Board Meeting 22-24 June 2010

Office of the Ministry for Children and Youth Affairs/BelongTo (2011). Addressing Homophobia: Guidelines For the Youth Sector in Ireland (Checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.belongto.org/attachments/233_Homophobic_Bullying_Guidelines_for_the_Youth_Work_Sector.pdf)

Reid, G. (2013). The Trouble with Tradition: When “Values” Trample Over Rights. (checked on 9 November 2014 on http://www.hrw.org/world-report/2013/essays/trouble-tradition?page=1)

Rogers. E.M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations. New York. TheFreepress.

Scanteam: Vik, I., Stensvold, A., Moe, C. (2013). Lobbying for Faith and Family: A Study of Religious NGOs at the United Nations. Oslo: Scanteam for the Ministry of Foreigh Affairs of Norway

SIECUS (2008). Mexico City Ministerial Declaration –“Educating to prevent”: Fundamental Principles and Tenets of the Declaration USA: SIECUS (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.siecus.org/_data/global/images/PAHO/PAHO-%20Tenet%20of%20the%20Declaration-%20FINAL-ENGLISH%20with%20NGO%20line.pdf)

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (2011). The Global Fund Strategy in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identities. Geneva: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

UNESCO (1960). Convention against Discrimination in Education (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=12949&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html)

UNESCO (1989). (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13059&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html)

United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/)

UNESCO (2011). Review of Homophobic Bullying on Educational Institutions. Prepared for the International Consultation on Homophobic Bullying In Educational Institutions, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 6-9 December 2011. Paris: UNESCO

(http://www.lgbt-education.info/doc/unesco/UNESCO_2011_Review_of_Homophobic_Bullying_in_Educational_Institutions.pdf)

UNESCO (2012). Educational Sector Responses to Homophobic Bullying. Good Policy and Practice in HIV and Health Education, Booklet 8. Paris: UNESCO

(http://www.lgbt-education.info/doc/unesco/UNESCO_Homophobic_bullying_2012.pdf)

UNESCO HIV & AIDS (2013). The Netherlands contribute €500,000 in support of UNESCO’s work to Prevent and Address Homophobic and Transphobic Bullying.Paris: UNESCO (Checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.unesco.org/new/en/hiv-and-aids/single-view/news/the_netherlands_contribute_EUR500000_in_support_of_unescos_work_to_prevent_and_address_homophobic_and_transphobic_bullying/#.VF-eXhbIfis)

United Nations (1976). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx)

United Nations (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, (CEDAW) (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm)

United Nations (1990). Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx)

United Nations Meeting Coverage (2010). General Assembly, Human Rights Council Texts Declaring Water, Sanitation Human Right ‘Breakthrough’; Challenge Now to Turn Right ‘into a Reality’, Third Committee Told. Sixty-fifth General Assembly, Third Committee, 28th & 29th Meetings (AM & PM), Also Holds Lengthy Exchange on Report on Sex Education ; Hears UN Experts On Torture, Human Trafficking, Extreme Poverty, Physical and Mental Health (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.un.org/press/en/2010/gashc3987.doc.htm)

United Nations (2014). The Millennium Goals Report 2014. New York: United Nations

United Nations (2014). UN at a glance. (checked on 9 November 2014 at http://www.un.org/en/aboutun/index.shtml)

Weymann, A. 2014: States, Markets and Education. The Rise and Limits of the Education State. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan